The magic of the Mountain-EVO research project

Five years ago, we started a research project to study how a ‘Mountain Environmental Virtual Observatory’ (Mountain-EVO) can orient decision-making in a rural community in the Peruvian Andes with the aim of reducing poverty. The EVO was conceptualised to link science, experience from rural people, and ancient wisdom.

It was not clear at all how we would do this, both theoretically and practically. I remember my colleague Zed Zulkafli telling me with a big smile on her face: “this is what we want to do but I really don’t know how we will do it”. Frankly, I think this was an important part of the magic of this experience. Our imagination was set free to explore and experiment; the ultimate mission of ‘reducing poverty’ was inspiring; and, after all, we all worked to protect water. The scientific advisors supported our proposals and, even though there was an interest in writing journal articles, they backed and put our proposals forward.

(Photo credit: Sam Grainger)

The Mountain-EVO project studied local communities in four mountainous countries in the world: Ethiopia, Kirgizstan, Nepal, and Peru. As expected, despite their similarities in adverse climatic conditions, poverty, and social organisation, each community showed their particular history and characteristics that make them unique.

Sharing the experiences that the diverse researchers in the four studied countries had was wonderful. For me, the instant connection we felt between the four female social researchers was particularly special. Sometimes I thought that it was ironic that we all four were women, whereas the natural science team members were mostly men. However, thinking about it, that was also part of the magic of the project. It was beautiful to discuss and think together on how to collaborate in our activities and, more importantly, on how it was important for us not only to generate publishable information but really to generate a positive impact on the communities we worked in. Beyond the project, our friendship is still strong and it is clear that, although the great geographic distances between each other, we will always support each other.

Where and why there?

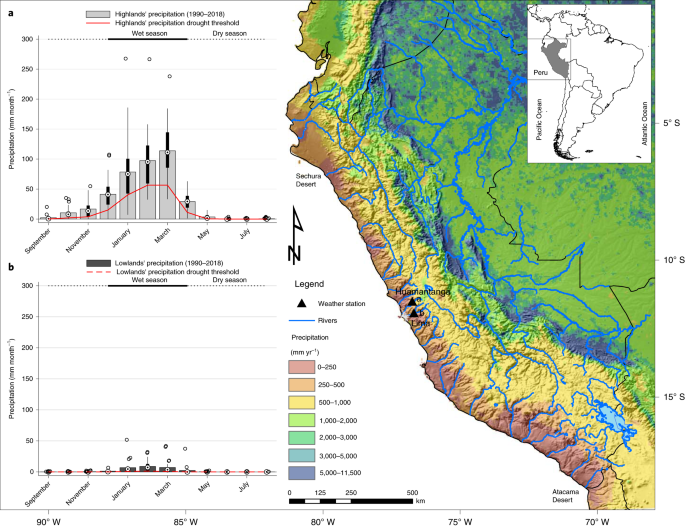

The community of Huamantanga in Peru, with approximately 600 inhabitants, mixes interesting characteristics to be analysed in the ‘Observatory’. They settle in a semiarid region that experiences water scarcity most of the year, for which they have developed an ancient water harvesting practice called ‘Mamanteo’. Mamanteo means breastfeeding in Spanish as, for most of Andean peoples, women are the guardians of water security. This tradition, which has been maintained for generations and centuries, provides them with water during a great part of the dry season. Their productive activities are limited by water availability, which worsens poverty and migration. Lastly, the community is located in the source headwater area of one of the river basins that provide water to the capital city of Peru, Lima. Lima is currently the second largest desert city in the world and thus it depends heavily on local water management practices.

(Animation credit:Boris Ochoa-Tocachi, 2019)

Huamantanga represents what most rural Andean communities live. Despite being so close to the big city (approximately 3 hours driving), the poverty gap between them is evident. I have observed, in some places, the abandonment of rural areas by their governments. I am not referring here to plain capitalism but, for example, to the lack of infrastructure that can adapt to harsh cold conditions (which indeed occurs in other countries); to the levels and strategies of education systems that can adapt to the needs of rural students and their daily routines; and to the largely needed technical assistance that can facilitate the lives of farmers, bringing universities closer to rural zones to improve local quality of life.

The local community members of Huamantanga (‘comuneros’) told us that their greatest challenge was ‘their lack of knowledge’, but we had actually observed the possess great knowledge and work willingness. We then understood that the Mountain-EVO was precisely an active research that could rescue and revalue ancient and rural knowledge, combine them with modern water science, and aim at reducing poverty. We worked for combining science with rurality and ancient with present.

Huamantanga has a very interesting mixture: ancient water harvesting practices, community-managed land and resources, traditions that are deeply rooted in their daily lives, a need to better understand and manage water, and people looking for better opportunities that can keep their children from migrating to the city. On the other hand, their social organisation is complex and difficult; there is rivalry between the two neighbourhoods that form Huamantanga; time and creativity are needed to build trust and promote participation; there is corruption, politic favours, and other issues. Personally, all these elements put our feet back on the ground. We learned not only about science and hydrology but also about their daily reality. This was not a simple job, and the impacts did not become evident within the three years that the project lasted. This has been a continuous process requiring effort and a sincere approach to rurality. This is what we tried to do.

What does the paper do?

The paper shows the multidisciplinary effort of the Observatory to understand, technically and socially, the ancient practice of Mamanteo. It transforms the collected data into calculations and models that evidence the benefits of ‘green’ infrastructure compared to those of ‘grey’ infrastructure as well as the potential of this water harvesting practice. At the same time, this shows the co-responsibility in water management between community members located upstream in the headwater source areas and urban inhabitants of cities located downstream in the lowland areas.

This paper shows how interesting it can be to conjugate natural sciences, social sciences, community participation, and ancient knowledge. It exposes scientists to an understanding and value of fieldwork and indigenous knowledge. It also shows people from the local community understanding the experiments in their own environment and feeling proud for their water management systems. Overall, it shows team work.

The key of our experience was the awareness of the importance of building bridges: between science and community, and between science and decision makers. This approach included walking their paths, listening to what they have to say, living their traditions, understanding their needs, calculating the scenarios that they are interested in, being creative to adapt information to be usable, used, and actionable, and observing continuously in order to try again and again.

And we will always keep trying.

(Photo credit: Junior Gil-Ríos)

The article in Nature Sustainability is here:

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

This is amazing Katya! I'm so proud of you and of the entire Mountain-EVO and iMHEA teams!

I agree! This piece is truly heartfelt writing and communicated the soul of the project. We achieved so much as a team, especially so in terms of individual growth.